How Cameron Kostopoulos' debut VR piece 'Body of Mine' became the most talked about XR exhibit at SXSW festival

And how it almost didn't premiere at all after the whole thing stopped working minutes before opening day ... I was there for it all.

It was there there, on the streets of downtown Austin, after driving 1400 miles from Los Angeles to Texas with a trunk full of virtual reality hardware, after maxing out credit cards and spending all nighters completing his first VR experience and then building a booth structure out of PVC pipe and chicken wire, that Cameron Kostopoulos, aged 24, finally collapsed into the arms of his friends who had been with him every step of the way.

In his hand he held the SXSW XR Special Jury Award - a large metal buckle attached to a plaque of wood - presented to him that night at one of the largest festivals of its type in the world.

Three days earlier, Cameron, a current ASU Masters student in Narrative and Emerging Media, was on the floor of a convention hall of the Fairmont Hotel. He and his team were furiously gluing, bending wire, and attaching blood red fabric to a structure that would form the three booths where his debut immersive work ‘Body of Mine’ would premiere to a global audience.

Directing the chaos was his friend and artist Taylor Woods.

“Here,” she says, handing me some scissors, “cut this fabric.”

Working around her, plugging in hard drives, VR gear and lights are some of Cameron’s closest friends - largely from his undergraduate film studies at USC. They had seen his directorial vision that had developed during the course of those studies. It was compelling.

Evan Siegal helped build and design the VR experience, Prateek Rajagopal composed the score, Ethan Denning and Cameron’s brother Ty, both came aboard to help run the VR stations.

The next day, Body of Mine would be open for the SXSW press day and the team were driven by the goal of creating the most impressive looking booth in the whole room.

Around them were about 30 other teams all building their own stations for various experiences that had traveled from South Korea, France, Ukraine, Germany, Britain, South America and China.

Hayley Martin, the XR coordinator for the festival, arrives and tells the teams to start packing up. It’s 5pm.

“You need to be out of here,” she yells across the room. “Go and party!”

Evan speaks so only the team can hear: “We are staying here till they kick us out.”

The team keeps gluing, keeps tying wire and I keep cutting fabric.

***

Body of Mine was conceived slowly over Cameron’s lifetime. But it came to the fore about two years ago when he was kicked out of home after being outed as being gay to his parents. Then, so was his brother Ty. Neither of them have seen their other youngest brother in more than a year.

“I got the ax,” Cameron says. “I got the typical queer in Texas story. I still don’t talk to my parents and I didn’t have a safe space. I thought ‘I don't have this but I want to build one’.”

The goal was to build something not just for him but a space that he could share with other people.

“With people who could use it, for people who don’t have the privilege of having safe spaces or support systems.”

And so the assembly began. Cameron calls it a ‘ragtag team’ of friends who heard his vision. They believed in him and the project, and so, they all signed on. It all started in Cameron’s bedroom, working on his computer.

“We have worked on Cameron’s projects before,” says Ethan. “They are immense, chaotic, incredible things that you just want to be a part of.”

There were a couple of problems. Cameron didn’t know how to build the space he envisioned in his mind. And he didn’t have the money to pay someone else to create it. He didn’t even know how he was going to pay his rent after being kicked out of home. So, he spent time learning how to use Unreal Engine - one of the most popular pieces of 3D software that is used to create video games, virtual worlds, and increasingly, movies.

“I just had an idea and a lot of energy and a lot of coffee,” he says.

A year later Cameron had taught himself to build his virtual world and it was accepted into SXSW alongside projects backed by some of the biggest tech companies in the world.

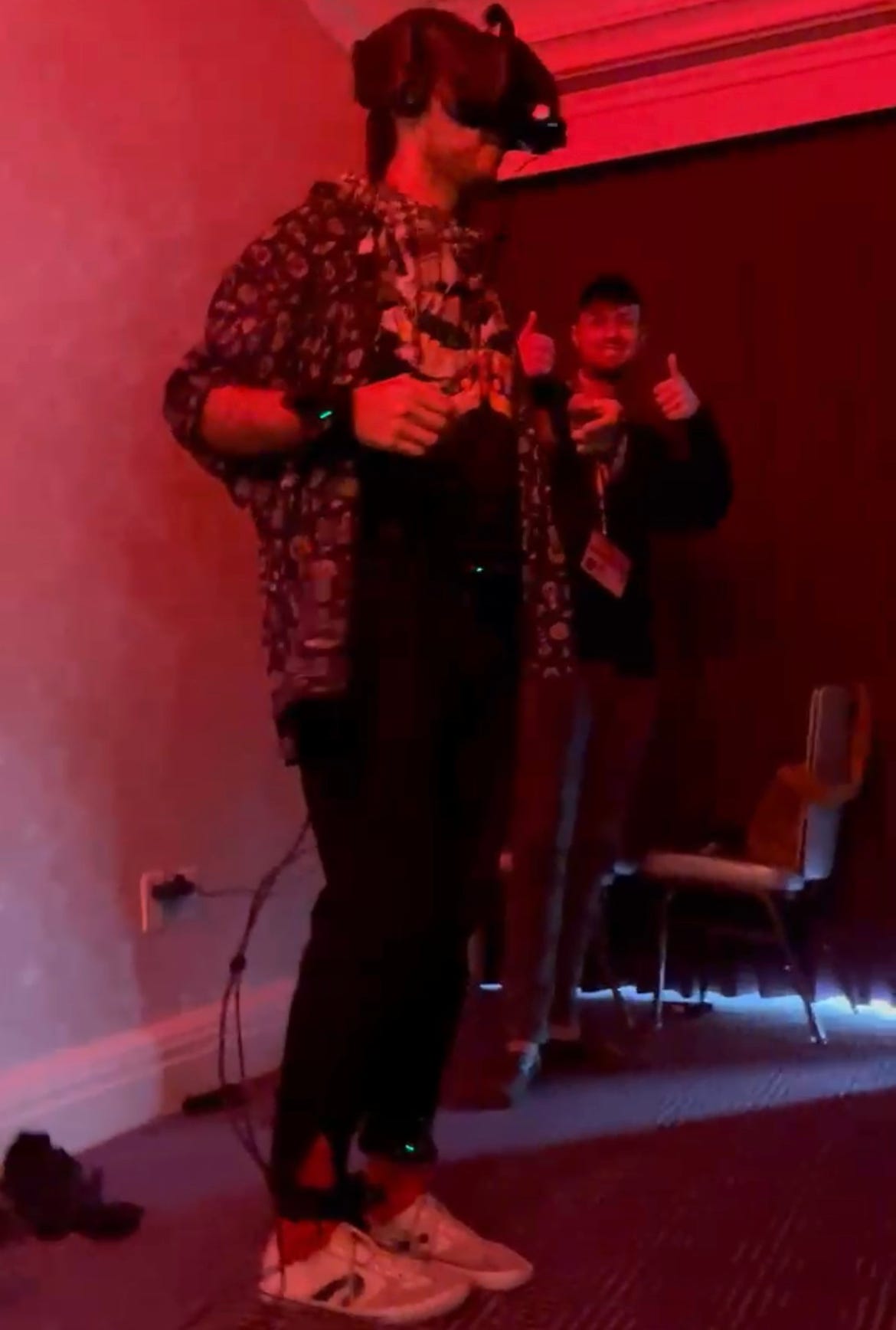

Cameron’s vision was a full immersion virtual reality experience which used HTC Vive tracking technology that attaches to different parts of your body as well as a headset that tracks your eyes. This effectively creates a live motion capture VR project where a user’s physical movements are mapped into the virtual space. Using that medium, Cameron then allows users to step into the body of a different gender. If they touch different parts of their body it activates interviews from people from the transgender community talking about what those body parts have meant for them in their life. It transports you into different stories, where the goal is connection and understanding - all using emerging technologies.

“It’s basically supergluing a lot of cutting-edge stuff into our own makeshift tracking system,” Cameron says.

“Because all of the pieces of tech exist in isolated pockets but there aren’t many experiences that combine everything to do a fully immersive embodiment of a body in VR.”

Look around in the virtual space and the whole experience occurs inside a human chest cavity with a beating heart beside you. There is a mirror - but when you look into it, you don’t see yourself, you see someone else. Your body movements are yours, your blinking and eye movements are yours but the person you see is not. You are fully immersed in a story that is not yours, transplanted into a body that doesn’t feel quite right.

If ever there was a case study to be made about VR creating a pathway to experience empathy, then Body of Mine might be it. Rather than walking a mile in someone else's shoes, it gives you 20 minutes inside someone's else’s body. The result is uplifting and illuminating and has different impacts on people depending on their own lives. It did the job Cameron set out to do … he thinks. But SXSW hasn’t opened yet and the first thing he saw when walked in was another project’s expensive 15ft LED wall and the tease of imposter syndrome crept in. There wasn’t time for that though. On press day, almost everything fell apart.

***

The ballroom on level 3 of The Fairmont Hotel is warm. Teams everywhere are frantically calibrating their projects to ensure that the media, who will move through the space in about three hours, will get the purest run of their piece. Perhaps they will write about it, perhaps they will tweet about it. The goal of SXSW is to get a next step - get the buzz, capitalize on the buzz then maybe make another festival, or a traveling show or permanent installation. It’s all a gamble in service of the sell.

Right now, the Body of Mine crew feels like they took the ultimate gamble. The tracking technology relies on clear, uninterrupted lines of sight where the trackers that are strapped onto different parts of the body can talk to the computer that is running the project. It’s sensitive. They know that. But they didn’t know that setting up in a room with more than 30 other exhibits all emitting their own various WiFi signals would cause issues.

“The trackers aren’t picking up,” Evan says, watching the screen in front of him for each of the seven trackers to be registered by the computer.

Each time they try to reconnect, several do come up blue (a good sign) before dropping off and fading in and out (a bad sign). If the trackers aren’t working during the experience it means that a person's arm or leg won’t be seen by the computer and will start to do weird things with their body parts.

“Taylor,” Cameron says, “can you Google it?”

She looks up, pulls out her phone, goes into one of the booths and begins the type of research that is so oddly specific that it only appears deep in nebulous internet message boards.

A few minutes later Taylor reappears. “I’ve found something.”

It seems that HTC trackers operate on a signal that is oddly similar to a certain type of WiFi signal which can cause issues. It’s so curious that even the HTC expert that arrives on scene isn’t familiar with it. It’s one that only rears its head in such an intensely complex environment as a festival XR hall.

The theory is that there is one exhibit pushing out a rogue WiFi signal that is causing the problem. The clock is ticking. In an hour the room will open to the press.

Cameron flags down Blake Kammerdiener, SXSW’s senior manager in charge of this part of the festival.

“We have a problem,” he tells him.

Cameron relays the theory to Blake who fires off myriad solutions to potentially try and block the signal, before bringing in an expert with a spectrometer that can see WiFi signals traveling through space.

Thirty minutes until the hall opens.

The theory needs to be tested so Blake tells the team to try to set up in the back corner of the hall, away from the signal. So they break down one of the stations and set up another one behind curtains that once was a rest area for registrants.

They fire it up. Cameron stands over Evan’s shoulder as he looks down at the screen. Ty puts on all the trackers and individually turns each one on.

The first tracker turns blue.

“Keep going,” Cameron says.

Another one turns blue.

“Keep going.”

Then another.

“Oh my god,” says Taylor.

“It's working,” Cameron says. “Wow.”

Before long all seven of them are blue and they are holding. For a while at least. Then … they all drop off.

The team has been working for almost 48 hours straight. They are exhausted and now, the media have begun to arrive.

In a last ditch effort, the team sneaks into a conference room across the hall to make sure that their supposed issue is the actual issue.

It’s all hands on deck. Ladders are shuttled in and out on shoulders. Cameron’s ASU Masters’ faculty in the form of SXSW hall of famer and VR pioneer Nonny De La Peña and technician Jet Olaño are facing down hotel staff who say that this solution can’t happen, as the room wasn’t booked. The hotel staffer tells them to get out before moving on. They are breaking the rules but they don’t go anywhere and continue with their set up. They will have to be dragged out of there.

If they can’t get the project working, it all will have been a waste. The possibility of giving up never crosses their minds - at least in public, not to each other.

“Sometimes it’s better to ask for forgiveness rather than permission,” Cameron says.

Blake appears and reassures Cameron that they will make it work. When the staffer reappears, they plead and beg with him to let them stay. He sees something in the desperation in Cameron’s voice and realizes it will be more trouble than it’s worth to go by the book. So they stay.

The team tests the booths and both of them work - each tracker glowing blue in the blacked out conference room. It’s a beautiful sight.

The press day is missed but Body of Mine has its space.

***

At 11am the next day the line running outside the SXSW XR space snakes down the hall. At 11.03am that starts to appear outside the Body of Mine booth. Within 15 minutes all the slots until 5pm are booked.

The big, red, glowing beast becomes the sign up tent. Then the mystery ensues as one by one people are taken across the hall, passed off to Evan, Ethan, Ty and Taylor in the conference room and taken through the experience.

Then they come back. Some are crying. Some want desperately to talk to Cameron, to thank him. There are mothers of transgender kids. People who identify as non-binary, people who have never given a second thought to the issue, all coming back wanting to unpack what they have experienced.

The panic of the previous day subsides and now it is just adrenaline to push them through all the bookings, two days in a row - back to back. There is an energy around the piece. Everyone who experiences it seems to love it. Everyone who didn’t seems to want to. In that way, Body of Mine and its ragtag crew create one of the most talked about XR experiences in the hall.

***

The team settles into their seats at the Paramount Theatre. It is the awards night for the Film and TV section of SXSW, of which XR is included.

There are awards for movie poster art, for best film, for music video and short film. Only a year earlier Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, known as The Daniels, premiered Everything, Everywhere All at Once at SXSW. A decade before that, they won best music video. Only a few days earlier they had won 10 Academy Awards. So this evening is permeated with significance. Who knows who in this room could be standing on the Oscars stage very soon.

Then the XR Awards slide appears on the screen.

Blake appears on stage.

“Our jury would like to give this award to this beautifully-crafted virtual reality experience that shows how VR can provide a safe space for understanding reflection and connection when a safe space in the real world is hard to find … “

Prateek looks around and simply mouths the words “wow”.

The team begins to realize.

Blake continues: “The Special Jury Award goes to … Body of Mine …”

The team rises - grinning from ear to ear, wooping. They all get up on

stage - each having had a part to play in this moment, from LA to Texas from bedroom to conference room.

Hours later, drinks have been had and war stories about the previous few days shared. At any one time, any one of the team could have shared their fears about the project, about the lack of sleep, about the seemingly endless number of obstacles in even getting Body of Mine working. But none did. Not once. There was an inevitability to this moment.

So there, finally, was Cameron on the streets of Austin letting that pressure go. The pressure that came with him and his brother being kicked out of home, from the work he put into willing his creation into existence, the pressure from paying for the gear, the accommodation, the fees for getting his team to Austin, and the pressure from not having seen his youngest brother in more than a year.

“I just miss him so much,” Cameron says. “I wish he was here.”

The group envelops him in a hug that is not easily escapable - a cocoon of arms and shoulders. Cameron found his safe space.