A Journalist's Handbook to the Metaverse: Part 2

The promises, pitfalls and opportunities of telling powerful immersive journalism

Dear readers,

This is the second of a two-part of report on immersive journalism that was facilitated by the University of Canterbury’s Robert Bell Travelling Scholarship and the Peter M Acland Foundation. You can read the first part here.

It is a deep dive into the what immersive technology might be able to provide for journalistic storytellers. As always, the landscape of this space is constantly shifting and has shifted still since this was approved for publication. But this report aims to offer a grounding in a world that will continue to have a part to play in how we experience reality, even if it is virtually. As always, I appreciate feedback, comments and questions.

My work in the U.S. has been based in Los Angeles. I was embraced by the immersive community there - so my thanks goes primarily to Nonny de la Peña for bringing me on board at Emblematic Group and helping developing Arizona State University’s new Narrative and Emerging Media program in DTLA. From there I have had the opportunity to work on projects as well as helping support award-winning work at SXSW in Austin Texas, in New York at Games for Change and finally the Venice Film Festival in Italy.

In all those places, people have been gracious with their knowledge and helped me understand how all of this technology might increasingly affect journalism. Some of them started talking to me in 2019 when the world didn’t know what was coming. The uncertainty about the future of this work, though, I believe is generally cause for enthusiasm.

Scaling Immersive

Despite the technological advances, immersive storytelling hasn’t experienced a steady upward curve in newsroom uptake. After the initial hype, many immersive teams moved on to other industries willing to fund experiments after tech collaboration dollars dried up.

Someone who knows firsthand the opportunity and heartbreak that can come with such decisions is Henry Keyser, who led Yahoo News’ immersive foray for several years before the department was shuttered.

His goal, rather than the previously cited examples in Part 1 of this report, which can take months to execute at vast expense, was to understand what it would take to make XR content on a daily turnaround.

“We are all still beginners in this field,” Keyser told me. “Most people working in the area have less than 10 years of experience.”

The approach to take on large marquee projects can have PR benefits for news organisations but the downside is much worse.

“Businesses want return on investment, not just buzz or awards. Being prolific, you can spread a number of eggs, you have more opportunity to find lightning in a bottle. You can also get good and useful data.”

What that meant by the end of Keyser’s tenure was that they had made hundreds of pieces of XR journalism content and had accumulated that data as to what makes a good piece of work.

He focused on making the decision makers at the news organisation aware of what it meant to be working in a 3D format, so they all spoke a common language. Stories would be conceived, pitched and produced within a silo so he would only be hearing about them when it was time of feedback. Keyser worked to be part of the early chatter about stories so that immersive ideas could be thrown into the mix when they were being developed.

Most ideas were simple augmentations of stories in the digital space. By the time he finished, the average cost of production was US$1000 and the traffic increase meant that the display ads often on these stories worked to offset the entirety of that cost.

“We accepted that failure was part of the growth process,” Keyser says.

Keyser’s main takeaway is that people increasingly have 3D capable devices in their pocket, so there is going to be an expectation that 3D content will populate that.

“I want to make sure that journalism isn’t left behind. We need lots of content because I want to consume this content in this format.”

One of his first projects, in 2019, was an Augmented Reality overlay, placing viewers inside the site of the Paradise wildfires in California.

“We felt a need to tell this story and thought there must be a way to use our AR technology to really bring people into this story in a new way.”

The project took 8 weeks to complete and approximately $30-$40,000 to build. But it only received a few thousand hits.

“While to XR aficionados it looked like a success, by any other metric it wasn’t.”

Over the next two years Yahoo’s price per unit dropped $1-3k per production and number of users went from app to web rose from 10k to 80k users with projects easily cracking 100-250k.

“That's when we knew we had established a functioning model.”

Keyser says the temptation with such projects is to swing for the fences. But that has a detrimental effect.

“For better or worse, there is a time to put up or shut up.”

For a long time there has been a promise that such technology will be a game changer for journalism.

“It has the potential power and impact that you can’t always get with other formats. But that does need to come up against business decisions.

“With immersive actually less is more. For most people this will be their first piece your audience experiences. You have to minimise what you are asking people to do.”

He found that the bare bones received high engagement. A project that was merely a 3D cut out of Vice President Kamala Harris with some key information about her reached more 100,000 people within a few hours.

“Is that what makes a good immersive piece? No, but it needs to fit a need at that moment.”

The unfortunate irony in this is that Yahoo’s library of immersive projects have since been taken offline, another blow to the work done in this space.

The New Zealand immersive experience

There have been a small handful of examples of news outlets in Aotearoa experimenting with immersive content.

New Zealand Geographic

In 2018, NZGeo launched its first VR project. Using specialised 360-VR video technology, a team from New Zealand Geographic—with funding from Foundation North and NZonAir—has produced VR experiences across six sites from Niue to the Hauraki Gulf. It now has a vast library of 360 video content.

Stuff Circuit

The now disbanded Stuff Circuit team launched the country’s first fully immersive virtual journalism experience. Requiring a VR headset or a smartphone The Valley placed audience members on the ground in Afghanistan to give you a sense of presence - a new level of understanding of what it’s like to be there, on the ground. It was an accompaniment to a deeply reported documentary series. The VR experience simulated events, based on official records, and interviews, giving users another way into the story.

TVNZ Under the Ice

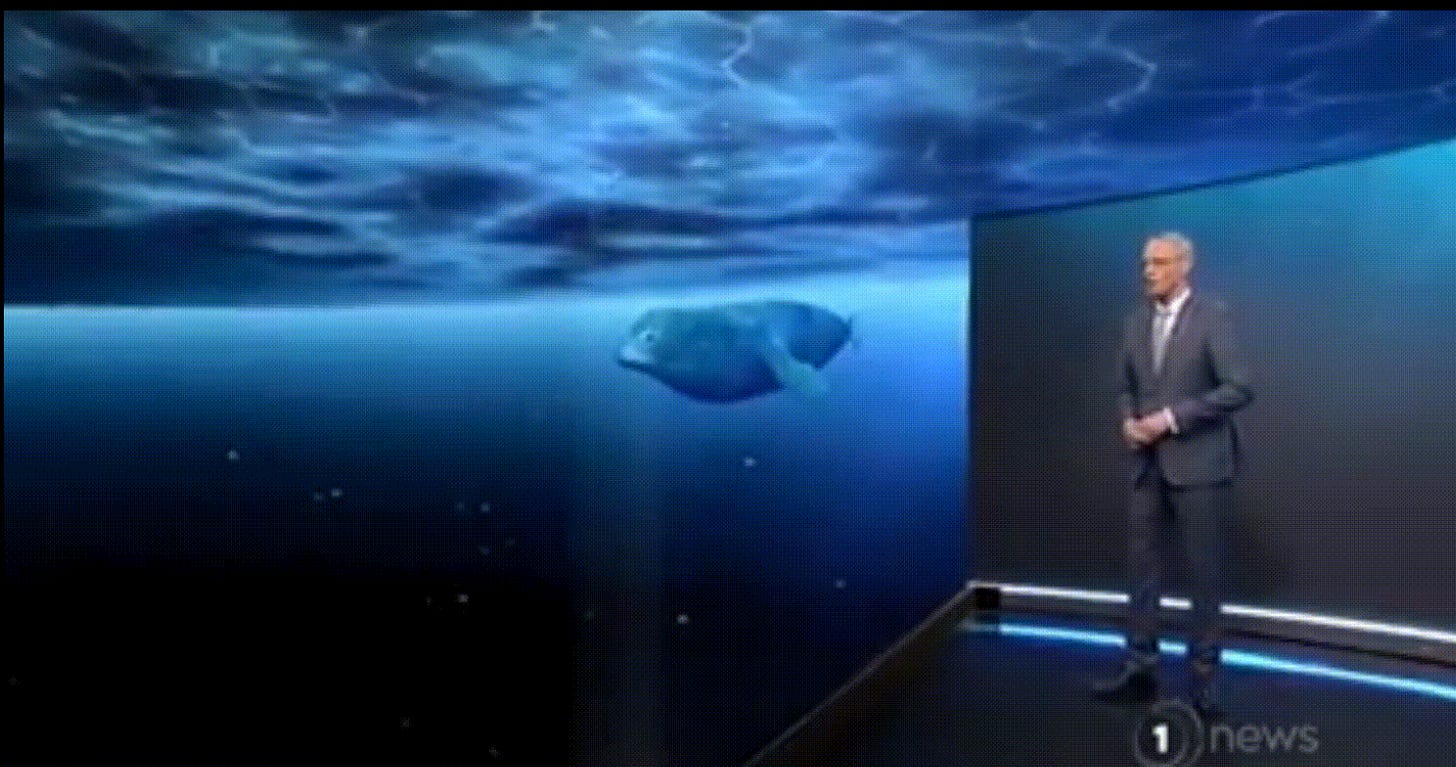

Answers Under the Ice is the result of a two-week trip covering science in Antarctica in November 2019. TVNZ’s Kaitlin Ruddock and Richard Postles spent two nights camping on the sea ice in McMurdo Sound with the K043 team. It was a collaboration between the news organisation, my own Vanishing Point Studio, the Science Journalism Fund and Antarctica New Zealand. It blended an online interactive utilising 3D assets created by TVNZ, 3D team. These assets were then used in a live broadcast on 1news utilising its AR newsroom capability.

Such projects can be complex, time consuming and expensive. As such each of these were, at least in some part, funded eternally as well as using man power from the news organisations. However, as technology becomes more ubiquitous the barrier to entry will increasingly be lowered.

Stumbling blocks in immersive uptake

According to Laura Hertzfeld, who was director of the XR partner program at Yahoo working with Keyser, and has a long career in immersive journalism, there are still obvious stumbling blocks to making such work easy to create in newsrooms. In her report for Journalism 360, she outlines it thus:

• Technology options and file format limitations. Creating AR is getting easier every day, but it’s still not seamless. No one has decided on the file format to rule them all, so making a choice for your organisation and sticking with it, whether that’s using Google’s Model Viewer or testing out AFrame and WebAR, or building something custom is key for now. But being flexible and being able to change as the industry changes is also important.

• Getting buy-in from your newsroom powers that be. The Journalism 360 site and these guides are a great place to start helping illustrate to newsroom leaders the opportunity and impact of immersive storytelling. Budget and resources are also key to making your point. The cost of these experiences has gone way down, most photogrammetry can be done on just an iPhone.

• The biggest question: How can this content generate revenue? We approach immersive content as part of a larger package for our stories -- an additional way for our sales team to support getting content sponsored. As the technology improves, ads embedded within the experiences will also soon be an option.

• Working with creative ad sales teams and packaging XR content. It’s important to think outside the box when pitching XR content from a sales perspective. TIME had great success with this on the moon landing project, thinking creatively about retro brands that would want to build off the 1960s theme of the experience. Ultimately, they landed Jimmy Dean as a sponsor.

• Avoiding the question: Why is this in “AR”? We are constantly asked ‘why is this in AR instead of a flat video?’ This isn’t the right question. Of course any type of story can lend itself to any type of treatment -- just think about movies based off books and the reasons one medium works sometimes better than the other. Instead we should be asking “How could XR help bring this story to life in a new way?” When working with reporters, it’s better to ask where they are having trouble or what they want to illustrate but can’t yet, to get to a more productive brainstorm about what makes a good immersive story.

Immersive Ethics

As media continues to evolve, journalists are faced with fresh opportunities to tell stories in innovative ways. This shift invites a reevaluation of what constitutes "ethical storytelling" in the context of new and impactful media. It's not about discarding established guidelines, but rather about carefully considering how we adapt industry standards to fit emerging tools and technologies, while also being mindful of the potential consequences of our decisions.

As part of my work with Arizona State University’s Narrative and Emerging Media program we worked to develop the bones of an immersive code of conduct or ethics. Other work has already been done in this field also but the basic premise is that the understanding of ethics in journalism remains but with this new technology there are other considerations at play. McClatchey’s Jayson Chesler and Theresa Poulson break these down thus:

Immersive media, which includes 360-degree video, augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and other 3D formats, brings unique challenges compared to traditional forms of media, necessitating a fresh interpretation of established ethical standards.

Audiences have increased control and agency.

These experiences, and how they are delivered, are often unfamiliar to both viewers and sources.

The psychological and immersive effects of these media are still being explored.

The process of capturing content requires extensive post-production work, such as repair and optimization, which goes beyond typical photo or video editing.

The technology comes with notable limitations and challenges that affect both user experience and creators.

Before starting an immersive project, it’s important to ask key questions to ensure thoughtful consideration of the potential effects on reporting, production, and the delivery of the story. These questions are designed to encourage deeper reflection rather than to inhibit creativity.

Production Considerations

Can the subject be accurately captured, or would recreating it be more effective?

Will a failed capture misrepresent the truth? For instance, photogrammetry is highly precise when inputs are correct, but could issues like incomplete photos or poor exposure lead to inaccurate visuals?

Is it necessary to capture the exact subject, or can a representation suffice? If direct capture is not feasible, can a model based on photos be used?

How will individuals be portrayed, and how might their depiction influence perception?

What are the best tools for capturing people? Is volumetric video distracting?

Could incomplete captures, such as only recording the front of a person, create a distorted representation?

Does the stillness of a photogrammetry image risk appearing too lifeless or unnatural?

Could photogrammetry inaccurately depict details like clothing or hair?

Is motion capture an option? If not, could stock motions compromise the truth by misrepresenting the subject?

Could the techniques used to capture people unintentionally dehumanize them, portray them negatively, or exaggerate/distort features?

How will you communicate with your subjects to ensure informed consent? Do they understand the full process and how their likeness will be used? Is there a need for them to sign a release that covers all these aspects?

Places and Spaces

How will spaces be captured, and how will you handle permission from property owners?

Could offering an immersive view of a space pose a security risk?

What approach will be taken with objects? Are you capturing essential details, and can they be accurately represented?

If the context of an object is significant, can you effectively convey that in its capture?

Controversial and Sensitive Topics

Could your immersive experience cause distress to viewers? How can you address this in your editorial process?

For AR stories, are you comfortable with viewers placing the story in any setting and potentially taking photos?

How can you prevent the recontextualization of your work? Similar to how statues may suggest reverence or memorialization, could a 3D scan imply a meaning or honor that wasn’t intended? How can you manage this in the way the story is presented?

How this works with Aotearoa’s current journalism ethics

There might be a temptation to think that this technology requires a total rethinking of how ethics would be applied in everyday journalistic work. But any new development in storytelling, the advent of video production or data journalism, for example, seems to adhere to the same basic tenets.

In New Zealand, the de facto journalist union E tū, and the two major news companies, NZME and Stuff, all have their own code of ethics. And of course, the Media Council has its statement of principles, which also covers the same ground. I will look at points in these policies for any potential pitfalls for the practice of immersive journalism.

What is specifically useful here is to look for principles which align with the capturing of photos and video. Often the same hardware and considerations are used for this capture as in immersive production. Stuff, however, goes a step further to include wider content creation, such as data journalism. It also defines ‘content’ as – “any published material, including text stories, videos, audio, photographs, data visualisations, and interactive designs”. Within this kind of banner immersive content ethics could easily be added in.

As suggested above the overarching journalistic principles of fairness, accuracy, impartiality should apply to immersive content. The more specific examples below deal in how this might be implemented. I have used statements from the Stuff editorial code of practice as catchalls for similar statements that are echoed in all organisations mentioned above.

Content Warnings and grief

“When a story contains material that is graphic, obscene or likely to offend our audience, we will include clear warnings. Such material generally should not feature in headlines, homepage or front page images, video previews, or other placements where readers and viewers are unable to exercise their choice to avoid it.”

“Journalists should approach cases involving personal grief or shock with sympathy and discretion.

Without restricting our ability to report newsworthy information, we should be mindful of the impact of the reporting process on people experiencing trauma. In particular, editors should consider the news merit of publishing sensitive videos or images - such as photos of houses or crash scenes - and consciously weigh up the public interest value with any countervailing factors of privacy or trauma.

Journalists should make best endeavours to ensure next-of-kin have been alerted before publishing the identity of someone who has died, except when the exigencies of significant news make that impractical.”

A long wrestled issue with immersive journalism is whether the creator will “allow the user to step over bodies”. In stories such as dispatches from theatres of war, or where the subject matter deals with death or tragedy, where is the balance between putting the viewer in the story, and being gratuitous? Content warnings may help but there may even be policies within news organisations that will expressly avoid these kinds of stories.

Nonny de la Peña recounts issues she had when she created “Project Syria”. The first scene replicates a moment on a busy street corner in the Aleppo district of Syria. In the middle of a song, a rocket hits and dust and debris fly everywhere. The second scene dissolves to a refugee camp in which the viewer experiences being in the centre of a camp as it grows exponentially in a representation that parallels the real story of how the extraordinary number of refugees from Syria fleeing their homeland have had to take refuge in camps. All elements are drawn from actual audio, video and photographs taken on scene. De la Pena says she had a huge push back on that scene from some viewers but also huge support from Syrians who had actually experienced it.

As in traditional news reportage, care in creating content warnings but also being sensitive to subject matter is of huge importance. The ‘conscious weighing’ of news merit of such stories still applies to immersive content.

Photography and videos

“Journalists must not tamper with photographs or videos to distort and/or misrepresent the image – except for purely cosmetic reasons – without informing the reader what has occurred and why.

Stuff avoids blurring or pixelating images or videos unless required to comply with the law.”

Here, the line can become blurry. Often with the creation of immersive content there is a necessary process to touch up the work captured in the field. 3D sculpting tools are often used to cut away unnecessary noise, or are processed in a way to make it usable for a mass audience. There is even a possibility that some elements may be added in to add to the fidelity of a scene or an object. As above there should be a clear heading saying what type of processing has occurred and why. And such processing should never distort or misrepresent. This kind of editing should only be for cosmetic reasons.

There are also pieces of work such as Yahoo’s content which used 3D models to recreate scenes - whether from January 6 or the Paradise fire pieces. It should be clear that the scenes are recreated and what information that it has been based on. In many longform pieces that try to use a novelistic writing approach where the sources are often hidden for stylistic reasons, the sources are used at the end of the article so the reader can be assured that all is based in fact. I have used this technique myself without ever any concerns raised by readers or the subject matter of the articles.

Privacy

“We strive to strike an appropriate balance between reporting information that is in the public interest and observing personal privacy. People have a right to a reasonable degree of privacy, and journalism should not unduly impinge upon that.

Information that is already in the public domain will not usually be considered to be subject to an expectation of privacy. The identity of a person carrying out their job is not a private fact, and neither is a person’s death.

As a general rule, videos or photos that are shot from public land – and therefore depict what any member of the public in the same position could observe – will not be considered a breach of privacy.”

Capturing immersive content covers the same issues that occur in modern day visual content. Videographers and photographers often balance the need for an image vs the privacy of individuals. They also might use drones, or long lens cameras to get their shot. Using drones for photogrammetry is often used for large scale objects or scenes. The same rules should apply.

Treaty of Waitangi

“We recognise the principles of partnership, participation and protection should help guide our actions.

Partnership: Māori and the Crown have a partnership under the Te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi. Our journalism should reflect this authority by including mana whenua, Māori organisations and people in our stories.

Participation: We should ensure Māori voices are present in our content, and increase the diversity of perspectives we represent.

Protection: Our dedicated Pou Tiaki section for Māori-focused or translated stories reminds us to include Māori voices in our stories and write Māori-focused stories in all rounds and regions, for all platforms.”

News organisations should approach this no differently than in traditional news capture. If it suggests a recognition of the Treaty of Waitangi then immersive content should be created in a way that also reflects this commitment.

Mis/Disinformation

It’s the year 2028. You’re wearing a headset, watching the news in an immersive format. The President of the United States is standing right in front of you. But can you be sure it's really the president and not a simulation reading a script crafted by a troll? Can you trust immersive journalists to uphold honesty and adhere to journalistic ethics?

These questions are becoming increasingly significant among journalists and scholars as media companies explore the potential of immersive content.

With the rise of misinformation, immersive journalism faces the challenge of ensuring the authenticity of its content. Additionally, the high cost of producing immersive journalism raises ethical concerns for some media experts.

The Ethics Of VR

Emblematic Group encountered an ethical dilemma in 2017. The company collaborated with PBS’ Frontline on Greenland Melting, a climate change story featuring a hologram of scientist Eric Rignot.

To create the hologram, they brought Rignot to its lab in LA. They debated whether he should wear normal clothes or cold-weather gear to appear more 'realistic' on the ice. In the end, they chose a light jacket.

While it is seemingly trivial, the question cuts to the core issue: VR’s powerful ability to create presence. The challenge is not to exploit this illusion. Things that are real and things that are not should be clearly conveyed.

In 2016, philosophy professors Michael Madary and Thomas Metzinger published a paper titled Real Virtuality: A Code of Ethical Conduct. They argued that VR, being a powerful tool for mental and behavioural manipulation, requires careful consideration, especially when used for commercial, political, religious, or governmental purposes.

“We need more research on the psychological effects of immersive experiences, particularly for children,” Madary stated. “Consumers should be informed that the long-term effects of VR are still unknown, including its potential influence on behaviour after leaving the virtual world.”

VR And Fake News

One significant threat posed by immersive content in journalism is the potential for fake news organisations and trolls to produce misleading immersive content.

Tom Kent, president of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, was one of the first to discuss VR journalism's ethical challenges. In a 2015 Medium post, he highlighted the need for ethical guidelines to address issues such as fake news, even before the 2016 presidential election.

“In a few years, VR might simulate news events so accurately that it’s indistinguishable from reality,” Kent said. For instance, “a VR recreation of a scene involving Putin or Obama could be so precise that you can’t tell if it’s real or virtually created.”

These concerns are being address with various bodies having a code of ethics or guidelines, mentioned above.

With the advent of ‘Metahumans’ or lifelike 3D recreations of real people this challenge becomes more acute. Much like the issues of tampering with imagery handled above - all content that has been manipulated in some way and the reasons why should be clear.

Intellectual property in immersive content

XR technologies are still relatively new, and many of the intellectual property issues they may provoke remain unresolved.

For years, items featuring brands, recognisable cars, weapons, and famous locations have appeared in immersive environments like games. Consequently, there have been numerous instances of rights owners raising concerns about references to their IP.

As immersive environments evolve to make 'reality' possible—whether entirely virtual or through augmented overlays on the real world—the frequency of these cases is likely to rise.

It is a grey area of the law. Alex Harvey, owner of RiVR - a virtual reality company that, in part, specialises in immersive content for cultural institutions and creating training for organisations such as the fire service, has been conducting his own experiment in this realm. His Sketchfab account is filled with objects that are both in public places and also in private institutions. He scans them, puts them on his account and then sells them for other creators wanting to use these 3D objects in their own environments. As of yet he’s has not been challenged on this but suggests down the track there might be some law that covers it.

For journalism, any concerns about IP would likely be mitigated by whether the environment is in a public place and what policies or laws cover the use of photography or videography within that space. With real people, who perhaps might be scanned and then used in a story, that would be easily covered with a simple release. Such a practice is not common in the news gathering process but is the norm in documentary or commercial projects.

It would be suggested that this sort of release is created for the use of people with the express notion that those assets are not then onsold in any form for commercial gain. This is despite news outlets selling photos or licensing video for differing purposes. When the landscape is clearer perhaps such an avenue might be interesting in terms of an extra revenue gathering operation, where appropriate.

Towards a reporter’s basic immersive workflow

The elephant in the room of the entire above discussion is how such concepts can potentially be implemented into a newsroom environment.

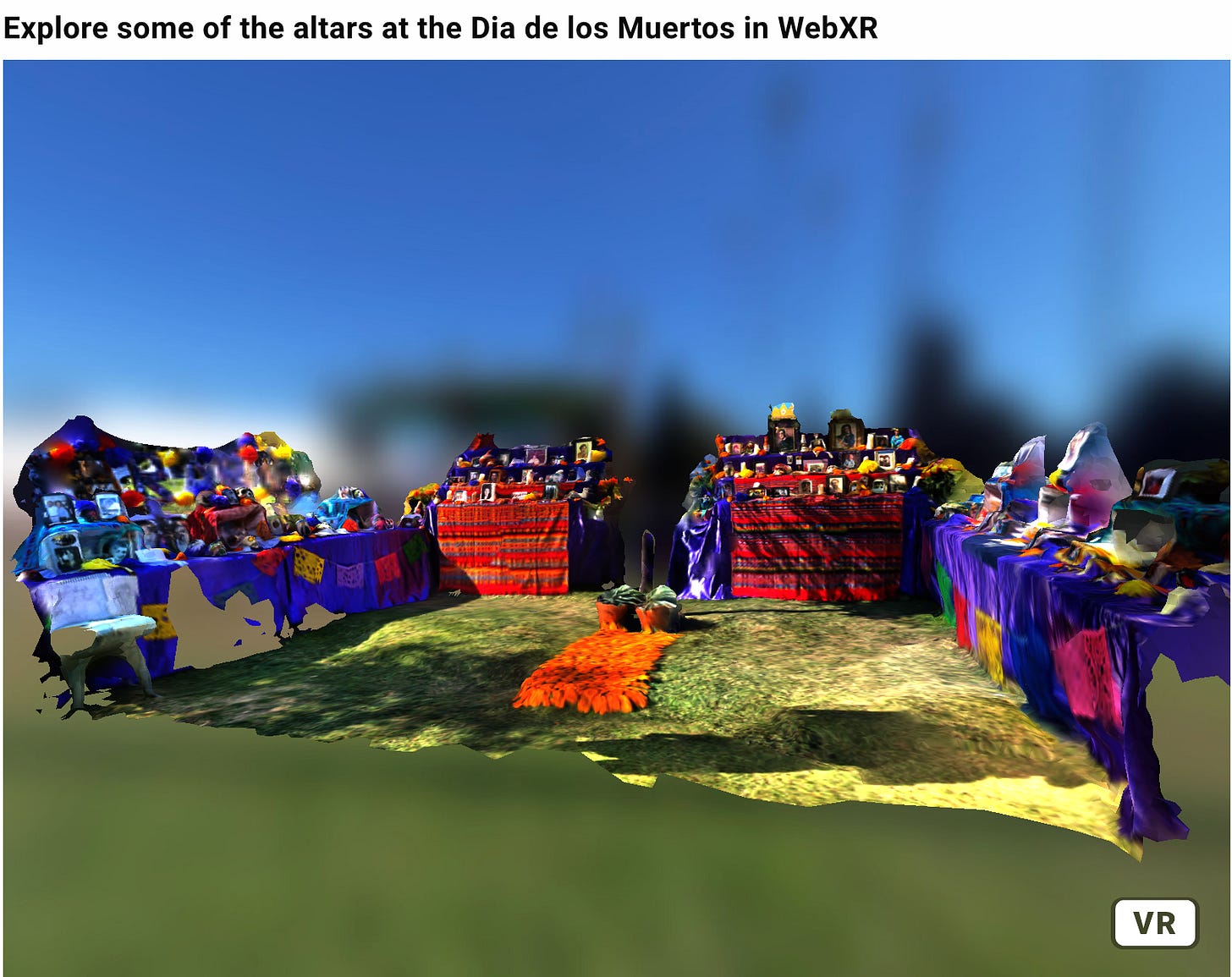

Last year I experimented with a workflow while on a simple story covering the Day of the Dead festival in Hollywood. The story was about the families who had come to the Hollywood Forever cemetery to create altars for their loved ones who had passed. Each was decorated lavishly and each had their own stories to tell. It is the sort of story you can imagine any small newspaper covering in a simple manner.

Instead, myself and Chimela Mgeuru went with an immersive lens. He with a 360 camera, and myself with my iPhone, and a photogrammetry app. With some light post production we were able to elevate a text and photo story with more assets that we hoped would allow audiences to understand a little more about what it was like to actually be there.

While capturing audio interviews with people from the event, I also used Polycam - a free app that unlocks both the LiDar and photogrammetry capabilities of your phone to create 3D assets. Simply scanning several altars using the LiDar function creates an asset in your app that can then be exploited as a 3D file. LiDar, however, does not do a great job of detail. Photogrammetry on the other hand - the practice of stitching together hundreds, sometimes thousands of photographs to create a 3D object, does. So I used LiDar to capture the altars and then photogrammetry to capture the winning dress of La Catrina, Jannan Beltran.

The 3D files I then imported into a web-based 3D engine I have been helping develop called REACH. Created by Emblematic Group, REACH looks to democratise the use of 3D storytelling by making it easy to build and then share immersive experiences online. Once you have your individual assets inside the engine you can place them wherever you would like, even uploading audio files to accompany, and skyboxes to fill out empty spaces etc.

When you publish from REACH it creates a unique URL that can then be embedded like any asset inside your website. The result is a simple way to offer more elements in your story that hopefully add to the richness of the story. The result can be seen here.

Immersive journalist’s toolbox

Polycam

There are four different ways to create a scan in Polycam. To scan objects and spaces, use either Photo Mode or LiDAR Mode. Photo mode is usually the best choice for objects where you want a lot of accuracy and detail, or if you don’t have access to a LiDAR sensor. It works by taking a sequence of standard photos and uploading them to a more powerful computer which creates the reconstruction.

Choosing your subject

Your object should have lots of surface detail and texture. Patterns, artwork, and organic surfaces work really well.

Even diffuse lighting is key to a good capture. If your object is reflective or shiny, try to diffuse the lighting as much as possible.

If the object is rigid, you can move it during your session, either by flipping it or rotating it. If you do move your object, make sure to flip the “Object Masking” toggle to on before processing.

To summarise:

DO choose subjects with lots of surface detail and texture

DO choose rigid objects (not floppy)

DON’T choose reflective and blank surfaces

DON’T choose thin, hairlike structures

How to capture

Photo Mode requires images of a subject from many different perspectives. Make sure to capture your subject from all angles. Take photos from above and below, as well as different sides.

Try to maintain at least 50% overlap between photos so that the system can register them. Not all photos need to encompass the whole subject. You can get closer and take more photos around detailed areas.

Remember to move the camera around the object. Great captures are made by getting a subject from as many perspectives as possible!

To summarise:

Take 25-200 photos (up to 1000 images with Pro)

Capture from all angles

Maintain 50% overlap between photos

Fill the camera’s field of view with the object

The resulting file can then be used in a variety of ways. They can be placed into platforms below like Spatial or Reach which can then be deployed into a headset environment or experienced on your phone or laptop or uploaded into Sketchfab to be used as an AR inset into your story through its platform.

Spatial

Spatial.io is an immersive social platform that connects global communities across web, VR, and mobile. It aims to revolutionise the way people interact, bringing art, culture, and creativity to the forefront of modern networking.

Objects that have been captured by Polycam can be uploaded into a Spatial space which then can be shared with audiences so they can all potentially walk around the same digital environment - either on their phone, desktop or even with a VR headset.

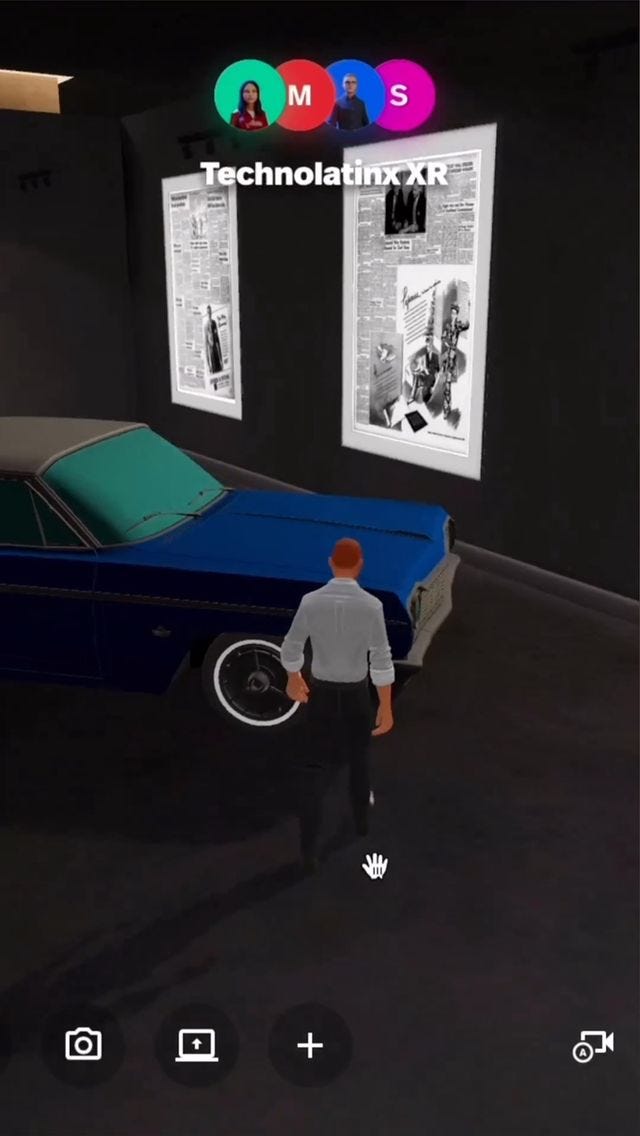

I created this workflow for an organisation called Technolatinx which seeks to empower young Latino in Los Angeles to learn immersive technologies.

A space was created where photogrammetry captures of objects which were close to the hearts of the creators were uploaded, along with newspaper articles that could be viewed on the walls of the space. Then members of the public were invited to wall through the space with their phones or headset to explore the creations. The potential to create shared immersive spaces showcasing journalism has yet to be created but offers rich opportunities.

Further newsroom development

These are some basic starting points to help implement immersive content into story gathering. A larger investment would be

Bringing in specialist 3D modellers/artists who can clean up captures by people in the field.

3D game engine developer with immersive experience - utilising Unity or Unreal - the two top game engines in existence to be able to create richer experiences.

There are people who do both and can also use engines like Snap Lens who could create AR filters for news story accompaniments.

The future

It’s obvious that most people do not have a headset capable of experiencing an immersive experience. However, almost everyone does have an incredibly powerful tool that is capable of capturing that type of content. If we think back to the advent of the iPhone in 2007 to now - the technology has galloped along at an incredible pace. We might well be in the iPhone gen 1 time now.

The AI revolution should form its very own Robert Bell scholarship topic which is why I have not touched on it until now. But it would be neglectful to not mention its impact on immersive storytelling.

ChatGPT, the popular chatbot from OpenAI, is estimated to have reached 100 million monthly active users in January, just two months after launch, making it the fastest-growing consumer application in history. It took TikTok nine months to achieve that.

Now AI technologies are being created that can offer speech to text to 3D asset creation. This cuts out much of the work a 3D modeller might do to create realistic scenes in which stories could take place.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been creating ripples across diverse industries, ranging from healthcare to finance. Now, it stands on the brink of transforming the realm of immersive storytelling. As technology progresses, the potential for AI-driven narratives expands limitlessly. This offers the prospect of crafting truly interactive and captivating entertainment experiences for audiences.

The notion of immersive storytelling is not a recent one; it has persisted for centuries in various manifestations, from oral storytelling traditions to theatre and literature. However, the emergence of digital technology has unlocked fresh opportunities for immersive storytelling. This enables creators to fashion narratives that are more interactive and captivating than ever before. With the ascent of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies, audiences can now find themselves transported into the realms of their preferred stories, undergoing a more visceral and personalised encounter.

AI possesses the potential to elevate immersive storytelling by enabling creators to craft narratives that are not only interactive but also adaptive. This signifies that the story can undergo changes and developments based on the actions and choices of the audience, resulting in a genuinely personalised and captivating experience. AI-powered narratives can scrutinise user behaviour and preferences, enabling the story to adjust and respond to the individual’s actions in real-time. This degree of interactivity and personalisation holds the potential to revolutionise the way we consume and engage with content.

Another illustration of AI-powered storytelling involves the utilisation of generative algorithms to produce procedurally generated content. This technology empowers creators to formulate expansive, intricate worlds that continually evolve and change based on user input and actions. This dynamic approach can lead to more engaging and dynamic narratives, as the audience actively participates in the story, shaping its outcome through their choices and actions.

This collision of technical advancements that the ubiquity of use of audiences expecting experiences to leverage these technologies will increasingly become the next space for stories to be told. The question is whether journalism will be able to keep up.