A Journalist's Handbook to the Metaverse: Part 1

The promises, pitfalls and opportunities of telling powerful immersive journalism

Dear readers,

This is the first of a two-part of report on immersive journalism that was facilitated by the University of Canterbury’s Robert Bell Travelling Scholarship and the Peter M Acland Foundation.

It is a deep dive into the what immersive technology might be able to provide for journalistic storytellers. As always, the landscape of this space is constantly shifting and has shifted still since this was approved for publication. But this report aims to offer a grounding in a world that will continue to have a part to play in how we experience reality, even if it is virtually. As always, I appreciate feedback, comments and questions.

My work in the U.S. has been based in Los Angeles. I was embraced by the immersive community there - so my thanks goes primarily to Nonny de la Peña for bringing me on board at Emblematic Group and helping developing Arizona State University’s new Narrative and Emerging Media program in DTLA. From there I have had the opportunity to work on projects as well as helping support award-winning work at SXSW in Austin Texas, in New York at Games for Change and finally the Venice Film Festival in Italy.

In all those places, people have been gracious with their knowledge and helped me understand how all of this technology might increasingly affect journalism. Some of them started talking to me in 2019 when the world didn’t know what was coming. The uncertainty about the future of this work, though, I believe is generally cause for enthusiasm.

It was 2019 when I first pitched for the Robert Bell Travelling Scholarship.

My proposal was to explore how immersive storytelling could be better leveraged by newsrooms to help the next generation of journalism with the next generation of technology.

The plan was to execute this during 2020. However, due to the coronavirus pandemic, that plan changed. Then, the technological landscape changed. And changed. During the coming years, AI would start to become an integral part of content creation. Platforms started making it easier to build immersive content. Tech companies, while ebbing and flowing with their enthusiasm, increasingly invested in hardware like virtual and mixed reality headsets that they saw as ushering in the next way to experience digital stories. Then, that ebbed and flowed back.

Two years later, I eventually travelled to Los Angeles to undertake the research. The promises that I forecasted in my original pitch had become clearer. The technology had become more accessible. Companies were investing in the idea that the next generation of computing would be ‘spatial’ rather than simply 2D. That is, we would experience the internet in 3D where people could communicate with one another across oceans as if they were really in the room. Those experiences would bring people together in a digital realm that was getting closer to the idea of being really there.

So the premise of the original proposal held up. But the more I thought about how this report might be useful, the more I thought that a straight academic project would not fit the bill. So this has become more of a guide - a handbook with case studies to the types of technology that now exists, what is promised around the corner, and how it might be easily deployed into newsrooms or journalism school curriculums without an incredible amount of heavy lifting.

For this project, I have been true to my background of liking to embed myself in stories before telling them. So last year, I immersed myself in immersive storytelling - helping produce projects, create software, learn from veterans, teach the next generation of learners, travel to festivals to learn and meet those at the forefront of this sort of work and about the technology that will facilitate it.

So this report is a synthesis of all of that work. While it doesn’t posture definite recommendations, within it are suggestions of what is coming and how journalists and newsroom leaders might better prepare themselves for that.

After all, most reporters of a certain age will remember when having journalists shoot video that could then be embedded directly into their stories was thought of as a fad.

You only have to look at the billions that have been poured into immersive content creation to see that Silicon Valley, Hollywood and storytellers of all stripes are not seeing the spatial future as a passive trend. While it might be some time before this kind of storytelling is ubiquitous, it will come and journalists should be prepared.

Why immersive storytelling?

I began my journalism career in 2008 when news companies had different staff for online and print, when satellite papers would hide stories from their parent’s growing national online presence so their front page could be a little more exciting for its few thousand subscribers, who would then receive their paper in the … afternoon.

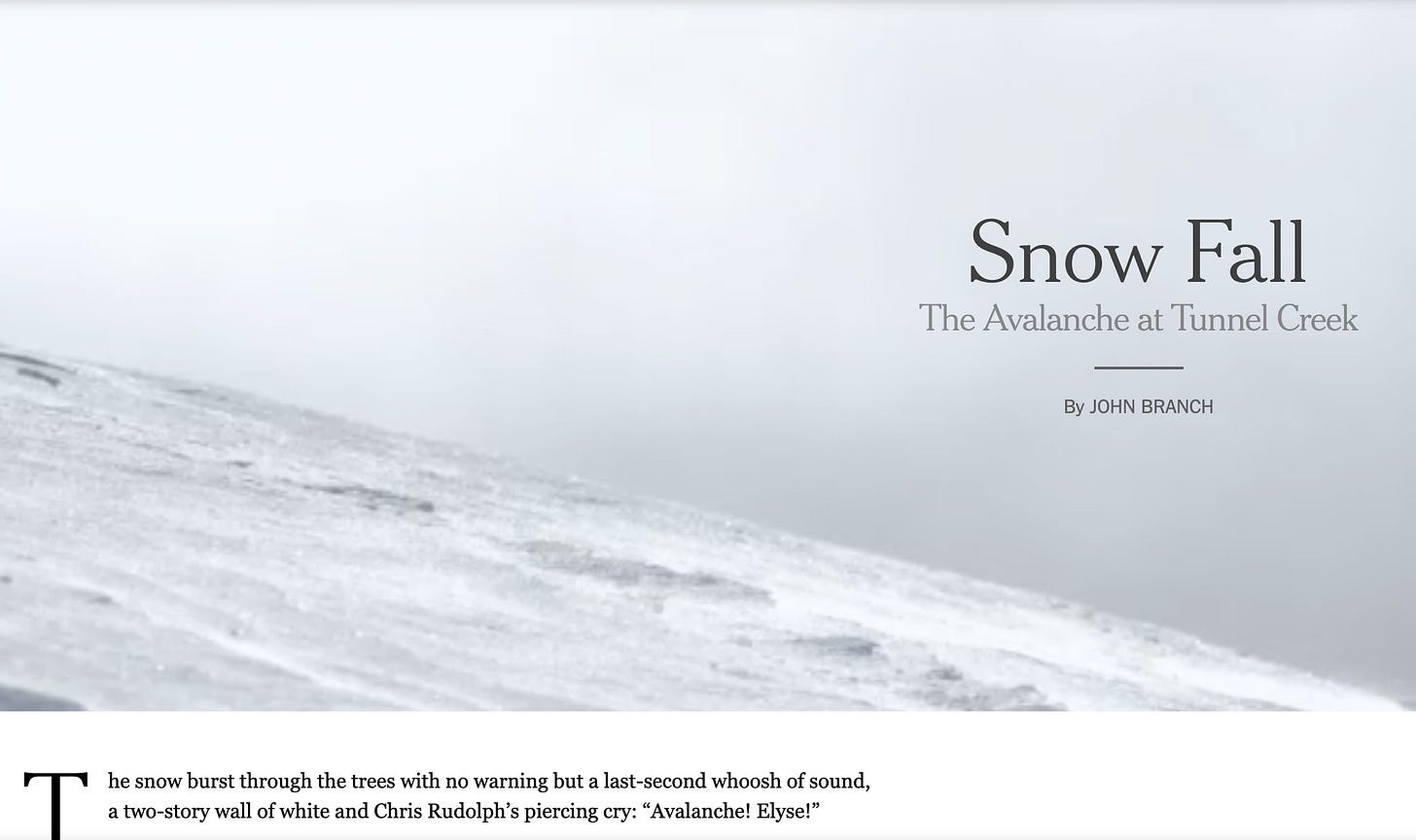

Times quickly changed. From online articles featuring some photos interspersed with text, I started seeing what the internet could do for elevating storytelling. I saw photographers learning how to take video, I saw print designers learning how to code. I saw John Branch’s Snowfall blending dynamic design, 3D mapping and data animation, and I was hooked. There was something about trying to place a reader in the middle of a story that felt right. Stories as experiences was not a new concept. narrative journalism had done this for decades - with words. Magazines used design, imagery and graphics to create a more wraparound story experience. But the internet had the ability to create that in new, exciting and achievable ways.

So, I started trying to create my own versions of these projects within my own company - then Fairfax New Zealand. I was a lowly intermediate reporter but I started reaching out to people within the company who were dotted across the country and whom I admired. A photographer/videographer, and a designer/developer. I put together a little team within a news organisation that started creating the sort of rich experiences that I hoped would blow audiences away.

The first of these efforts still exists online. It was about the search for a missing plane that, if found, would rewrite the country’s aviation history. I went all in, hiring an ex-Washington Post editor to help. It featured elements that, back then, could not be found in online journalism in Aotearoa. I still love it, but … we have come a long way.

From there I started my own digital studio, Vanishing Point, with an old friend who had forged his own career as a designer and developer. We wanted to create these sorts of experiences for media companies and brands and corporations all looking to place their audience in a rich digital storytelling experience. We worked with editorial clients from RNZ to TVNZ to Stuff and North and South, as well as myriad brands. Many of these were went up for Webby Awards alongside global news outlets like CNN, Vanity Fair and Forbes. We still pride ourselves on building projects that are at the forefront of technology and storytelling.

But that forefront always was, and still is, moving exponentially fast. It’s hard to keep up. From using game engines, LED volume stages, volumetric capture, mixed reality, AI, there are now myriad ways, with myriad jargon to tell stories that would have made this junior reporter from 2008’s eyes bleed.

The idea of this report is to make sense of this emerging landscape for newcomers, for the general reader and most importantly, for the journalist. There are plenty of resources out there for people who know all about these technologies and have in-depth knowledge and skills I likely will never have. But to understand what is coming and how it might be used will be of increasing importance to anyone who wants to start telling stories in new ways with emerging technologies.

I would note, that I have steered away from covering explicitly the impact that AI will have on the creation of content in this space. That topic deserves its own report.

What do we mean by ‘immersive’

“Immersive” has become a word that captures all manner of fields in this space. In 2023, it points to the collision of advancing technology and experiences, whether in person or through a device. It points to the idea that digital experiences currently accessed via traditional means like a website, a streaming or social media platform, or app (think Netflix, Facebook and your online news outlet) will increasingly become ones where a user can be placed within that experience.

There, they might be to able to see their favourite artist in concert without actually going to a concert, they might be able to touch an object without it really being there. They might be able to translocate that digital experience via a device into their own home so they can look around it on their kitchen table. They might be able to meet their friend who lives across the ocean for a coffee - each in their own location, but seeing each other almost as if they were really there.

‘Might’ is a loaded term here. These things are already happening and have been happening for years. But these experiences will become better and wider reaching, along with the expectations of a younger demographic that is unbound from the notion of how far things have come and how fast things are moving. This demographic is increasingly and unflinchingly adopting these means of interaction and entertainment as staple. So it’s worth taking notice.

Effectively, I see the word ‘immersive’ as touching on the vast trajectory of the next wave of communication. In the same way that the newspaper, then the telephone, then the internet, then social media all ushered in huge changes in the way that humans communicate, the immersive revolution is next.

Why?

For better or worse, we know that people like to gather. Once upon a time, that was forged by the need for safety in numbers - mainly by building communities around shared interests and values. A family, a club, a religion, or a local bathhouse all serve these purposes. Now, that gathering can be much easier to organise in digital social spaces like Facebook, Twitter, TikTok. In those spaces people like to communicate and share their feelings, thoughts and beliefs. The scale that these platforms provide can create vast energy from both individuals and groups. As we know, that energy can be immensely positive, or the polar opposite.

Since the first 3D game emerged in the 1980s, we also know that people enjoy entertainment in immersive spaces. The growth of Fortnite, Roblox and Minecraft all reveal the human urge to explore, compete and play in canvases that can be moved through, built upon, redesigned and discovered.

The continued development of these respective fields seems inevitable. And that development will lead to an eventual collision of these trends where a large part of digital social interaction is taking place in shared immersive spaces. Within that context, all industries will need to adapt the way they reach new audiences and customers. Entertainment, healthcare, workplace training, conferencing, retail - all these industries are already creating work utilising this type of technology.

The trajectory is nothing new. But the impact on the larger global population is not yet realised. What is missing is the wider uptake - both of technology to facilitate these experiences and then understanding of how these experiences work.

We all had a friend who got a thing called a Facebook account in 2005 with most not knowing what it was. Twenty years later, the impact of that (for better or worse) cannot be denied. I believe that we are at a similar intersection - but where the advancements will be much quicker.

In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell patented a telephone. It took 100 years for the first cellular phone call to be made, 20 more years in the 1990s for the first commercial calls over the internet to be made. Thirty years later, almost a quarter of the global population use WhatsApp as a daily communication tool.

The advancement of the immersive revolution has had stumbles. Companies that have been incredibly bullish and pioneers in this space have had missteps. In 2023, Meta (owner of Facebook) laid off 11,000 people in the wake of tumbling stock prices after investing billions into the development of its vision of the immersive future. Snap, laid off more than 6000 employees, and the ground is littered with startups which have failed to align their product with the timing of the boom in consumer uptake. But that is coming.

The largest companies in the world are pushing the boundaries in spite of these warnings. Apple has launched its VisionPro headset this year which allows Imax-esque visuals to be achieved in your own living room. Its latest iPhone is able to shoot 3D video that can then be played back within the headset to create a sort of fidelity and closeness that has never been achieved before. A journalist recently called Apple’s recent work in this space as a move to build itself into a ‘memory company’ - where life moments could be accessed and achieved in 8k resolution. The potential implications of this mission would be hard to miss for a journalist dedicated to capturing history as it happens.

This is how all advancement always occurs. That advancement can be overwhelming to understand, prohibitively expensive, and will throw up all kinds of ethical issues as to how we want to interact in this world and what dangers may occur.

What is clear is that when a large base of consumers understands what can be created when you think spatially, the path will widen to the creation of some incredibly valuable immersive experiences. And that is what this report is about - how it might be applied to the practise of journalism.

How can journalism be ‘immersive?’

Nonny de la Peña channels famed war correspondent Martha Gelhorn when she explains the idea of ‘immersive journalism’. Gelhorn called her collected writings ‘The View from the Ground’. That is, the best journalism was about placing the reader or the audience in the action so they could experience it as close to the real thing as possible.

“What if I could present you a story that you would remember with your entire body and not just with your mind?,” De la Peña says.

For her whole career as a journalist, she has been compelled to try to make stories that can make a difference and maybe inspire people to care. She has worked in print, documentary and broadcast.

“But it really wasn't until I got involved with virtual reality that I started seeing these really intense, authentic reactions from people that really blew my mind.”

One of De la Peña’s first forays into this world was a project called “Hunger in LA”

The premise was that Americans are going hungry, food banks are overwhelmed, and they're often running out of food.

“Now, I knew I couldn't make people feel hungry, but maybe I could figure out a way to get them to feel something physical.”

A producer went out to a foodbank line and recorded the desperation of those waiting to be fed. They took photos and audio of the scene and then, while documenting, a man had a diabetic seizure in the middle of the line.

They reproduced the scene with virtual humans and put the experience into a virtual reality headset. The piece ended up being the first virtual reality work to premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in 2012.

The reaction was singular. Over and over audiences who experienced Hunger in LA would act as if they were there on the scene. Some bent down to the ground trying to comfort the man, others experienced deep emotional reactions.

“I had a lot of people come out of that piece saying, ‘Oh my God, I was so frustrated. I couldn't help the guy,’ and take that back into their lives.”

Immersive Journalism was born. But this was in a time when virtual reality headsets hardly existed. De la Peña had to build her own - with the eventual founder of Oculus, Palmer Lucky, who later sold his company to Facebook for USD$1 billion.

Comments on her projects have circulated around a familiar theme: “It's so real,” “Absolutely believable,” or, of course, the one that I was excited about, “A real feeling as if you were in the middle of something that you normally see on the TV news.”

“Now, don't get me wrong -- I'm not saying that when you're in a piece you forget that you're here,” De la Peña says. “But it turns out we can feel like we're in two places at once. We can have what I call this ‘duality of presence’, and I think that's what allows me to tap into these feelings of empathy.

“So that means, of course, that I have to be very cautious about creating these pieces. I have to really follow best journalistic practices and make sure that these powerful stories are built with integrity. If we don't capture the material ourselves, we have to be extremely exacting about figuring out the provenance and where did this stuff come from and is it authentic?”

I worked at De La Peña’s company, Emblematic Group, while also helping set up a new programme at Arizona State University’s Masters in Narrative and Emerging Media.

We have worked on everything from an augmented reality documentary on the 1906 Atlanta Race Riots to a Virtual Reality experience based on a retelling of the most famous home run in Los Angeles baseball history in 1988. Here, the medium allows the user to be inside the story, experiencing history as only immersive technology might allow.

A glossary of immersive terms

I thought it might be helpful to lay out a glossary of sorts to give readers who are less familiar with this space a bit of an introduction to what life on the technological horizon is increasingly looking like.

Metaverse

Metaverse is a word first postulated by a sci-fi novel called ‘Snowcrash’, where rich people escaped the drudgery of their everyday lives in a new, exciting digital realm. Mark Zuckerberg is a fan and a true believer in its concept. So, in succession, brands and consultants started hiring Metaverse officers. Facebook even changed its name to ‘Meta’ in October 2021, in preparation for this impending reality.

But here is the thing. The thing is not a thing. There is no such thing as a Metaverse … yet. What that thing is in theory is a digital world - where we can strap on headsets (or not) and live our lives in all facets in interconnected virtual spaces where the same issues that plague humanity may or may not exist.

Fashion will and does exist in the Metaverse. Exorbitant property prices look like it will exist. Snoop Dog might even live next door. The below is a music video he shot depicting his virtual home in a virtual space called Sandbox. This guy paid US$450,000 for the privilege to be his virtual neighbour.

So, yes, egos will also definitely exist. But it will bring on an impressive way to communicate across distances and have experiences that cannot be had easily in real life.

It is science fiction, made fact, and elements of it already exist and have existed for some time. When spaces like Sandbox are connected to others and moving between them becomes seamless, that is when a vision of a true ‘Metaverse’ might be a reality. No doubt it will come with the same opportunities and troubles that currently exist with the current version of the internet. Think of it as an immersive internet where you can live in a browser and explore everything the internet has to offer, in the round … both good and bad.

NeRF and Gaussian Splats

It’s not a foam bullet gun. A NeRF or ‘Neural Radiance Field’ is a way to render fully realised 3D scenes from 2D imagery. The technology uses algorithms to effectively fill in the gaps between 2D images. It means that you can create a 3D scene that you can move through or fly a camera shot through. Gaussian Splats uses a different mechanism to create even more impressive results.

What started as people experimenting capturing fire hydrants has now morphed over the space of a couple of months into McDonald’s using them for an TV advertisement. The tech is set to disrupt the film, TV and immersive entertainment industry by making it incredibly easy to create 3D scenes with not much more than your smartphone camera.

AR

AR or ‘Augmented Reality’ is a term to describe overlaying something digital into the physical realm. As described above, Pokémon GO might be the most widely used version of this.

Here, you are using a device like your phone, a tablet or a headset of some sort where you can see the physical world through the viewfinder but digital objects can then be placed within that viewfinder. Beyond games, big tech is banking on AR more now than VR as a way to generate revenue. The technologies are already being used for things like workplace training. But work is already underway to allow phone users to point their device at a shop or a food product and have information pop up about what might be inside. Or you could be shopping for an outfit on your phone and then have a digital model walk out to show it off for you.

Then there are the big business applications. The U.S. military recently awarded a potential 10-year $20 billion contract to Microsoft’s headset, the ‘HoloLens’, to roll out its product to army personnel. These were described as “high tech combat goggles” … which sounds … interesting. However, that Magic Leap, which was also pursuing that contract, is selling its wares to healthcare companies that might see doctors using AR to perform simple or complex surgeries.

WebAR is a way to deploy the above experiences but using an internet browser, meaning the users does not need to download an app for have any sort of device other than a smartphone.

VR

Before he was James Bond or the wannabe step dad in Mrs Doubtfire, Pierce Brosnan was a mad scientist who wanted to give greater intelligence to an intellectually disabled gardener by transporting him into a virtual realm. Directed by Brett Leonard in 1992, The Lawnmower Man was a dystopian vision about the promises and dangers of virtual reality. Not long ago I met Brett at a dinner and he is still working in the field of film and VR. It seems the potential horrors didn’t outweigh the potential benefits.

With VR, a person puts on a headset and is totally immersed in a digital space or an experience. They generally cannot see the physical space around them. The idea is that a user can be entirely transported into another realm. It could be calming meditation, or a terrifying horror experience, or a multi-person game where everyone is running around in the same digital space trying to shoot each other.

Or they could just be working from home. But how this ties into the Metaverse from above is the creation of VR spaces where you can communicate with others who also login to the same space. Perhaps you want a weekly catchup with your school buddies who now live across oceans. Or fully beam your grandma into your daughter’s first birthday, rather than just a 2D video. Versions of this are already possible and the boundaries are continuously being pushed.

XR

XR or ‘extended reality’ is a catchall term for all the other Rs - VR (Virtual Reality), AR (Augmented Reality), MR (Mixed Reality). It is the umbrella term for experiences that generally require a device of some sort to access.

3D engines

Whether you have played a video game, or watched a movie recently there are chances that part of it, or all of it, was created using a 3D engine. These are basically editing softwares that allows creators to build scenes and animate them in 3D - all in realtime. You generally don’t have to wait to see the result of your work render out. You can give certain objects triggers or rules and then link them all together, which how video games are built - even ones that are 2D.

There are two main players in this space - Unreal, which is owned by Epic (which in turn owns the mega game Fortnite) and Unity (which recently purchased Weta Digital for US$1.6b.

Filmmakers, creators, architecture firms, NASA, have been using this type of software for years but the technology is getting better and better. Things are getting faster, and uses are becoming vaster. Both the above companies have also made a real play at making the use of Metahumans a thing. These are 3D characters that look ridiculously realistic which can then be manipulated and animated in the engine to form part of any digital project you can imagine.

Haptics

Once upon a time it was the buzz you felt via your controller when you got sniped while playing GoldenEye on Nintendo 64 (as long as it had a RumblePak installed).

These days it's slightly more sophisticated. Haptics the field of fooling the body into thinking something is there when it really isn’t. Perhaps you want your game players to feel like they are really holding a door knob as they enter a room, or feel rain on their hands. Or feel pain.

Here haptic devices shorten the gap between feeling something in the physical realm and in the digital realm. Not too long ago I was shown a device from a Japanese startup called Miraisens which has developed a way for its technology to convey complex touch feeling. It could manipulate vibrations in such a way that you could feel pressure, the feeling of roughness if you run your hands over digital sandpaper, the feeling of your hand being pulled or pushed if you see a correlating image on a screen.

Unsurprisingly, this is a huge element of immersion but also has incredible applications for people living with disabilities. If you are deaf blind, for example, the ability to communicate to someone through Haptics open up lines of communication that did not previously exist.

Headsets

These are one of the mechanisms to access immersive experiences. Virtual reality headsets are being built by everyone from Meta (formerly Facebook) which bought out a company called Oculus in 2014 for $2 billion to ByteDance which owns TikTok.

As mentioned above, the boundaries of AR headsets are increasingly being pushed. Far from this notorious AR glasses takedown from 2013, the technology has come a long way and will likely become a more ubiquitous use for immersive experiences. Because it's hard to make strapping a cumbersome VR headset to your face cool, but AR headsets could be ok … maybe.

Virtual production

If you have watched The Mandalorian, Dune, Loki and … well pretty much most modern day shows or movies they may have had some element of virtual production. This is where software like Unreal is used to create the scenes needed for a shoot but then a cinematographer can physically move around that digital space with a virtual camera. You can see that play out in the below video of the ‘live action’ Lion King movie.

The other main element to virtual production is the increasing use of giant LED screens to replace green screen, set building or shooting on location.

Scenes can be put on to these giant screens, known as ‘volume stages,’ behind actors who are performing as if they are on a far away planet. Unlike green screen, those actors don’t need to pretend quite as much, as they can actually see the scene on the LED screen. And unlike green screen, all the effects don’t need to be put in after shooting - they are already there live in the shot.

This gives incredible flexibility to filmmakers who now can have a golden hour sunset for the entire day, rather than a couple of minutes. They can also manipulate the background in real time if something doesn’t look right. Put another boulder there, take out that tree, or change it out entirely for another set.

While the screens cost a fortune and Amazon has just invested in the biggest one out at 80ft! The idea is that, despite the huge cost of such a screen, the efficiencies created will offset the cost of flying an entire cast and crew out to say … New Zealand to shoot a whole film.

Volumetric capture

If you are going to try and have an immersive experience - whether that’s in Augmented or Virtual Reality - then you are going to generally want to walk around. And if you are going to want to walk around you are going to want to have characters or objects in the space that aren’t just flat 2D images.

But how do you do that? How do you film a human in 3D? Enter volumetric capture.

This is a stage which features dozens of cameras all firing simultaneously, all capturing the object in the middle at the same time. Through a very complex process those captures are all stitched together to form a 3D moving image.

That moving image can then be used for any number of uses - from immersive concerts, VR trainings, or taking a selfie with a fully-realised knife-wielding horror character. Anywhere you need a real person in 3D.

How this tech is being used in journalism

CASE STUDIES

I have already touched on one of the first teases at the future of immersion in journalism - Snowfall showed how graphics and design could pull a user into a story in ways that traditional text, photography or video could do. But since then the New York Times has been at the forefront of large-scale experimentation in this realm.

Reopening Classrooms

The newsroom was instrumental in showcasing the use of 360 video for stories that required an audience member to be placed in the centre of the action. The first 360 video documentary by The New York Times explored the global refugee crisis through the stories of three children.

In November 2015, it launched The Displaced and its virtual reality application “NYT VR,” distributed one million disposable Google cardboard VR headsets to its subscribers.

Since then, it has continued to experiment in this realm, forming an R and D department to explore the boundaries of what it now calls “Spatial Journalism”.

“We live in a 3D world, but most of our interactions with the digital world are still in 2D,” its precis reads. “Recent advancements in AR and VR hint at a shift toward interacting with digital information in 3D as much as we do in 2D. We’re interested in how the shift to spatial computing may impact journalism.”

Its moves in this space are predicated on the notion that storytelling is “not going to be on a sliver of glass forever”.

Their team features designers, developers and strategists all dedicated to looking at how the Times’ reporting can be elevated by implementing immersive technologies.

Matthew Irvine Brown, a designer based in Los Angeles, has been helping the Times develop some of the projects that are now lauded for their innovation and impact.

Part of this was helping how the NYT might adapt if spatial computing platforms become mainstream in the future.

He came up with several applications that are worth considering, and ones the Times has deployed in various ways.

“Probably the main way we get our daily news is during the breakfast morning routine, whether it be in print, an app or a podcast. If we were to sit at a kitchen table and use a spatial interface, what types of information and interaction design might be possible?”

While some stories work well as 1:1 fully immersible virtual reality experiences, what happens if the story requires more space than you have in your living room? Brown came up with the idea of a responsive layout that could adapt to space - whether it be a room or an outdoor space.

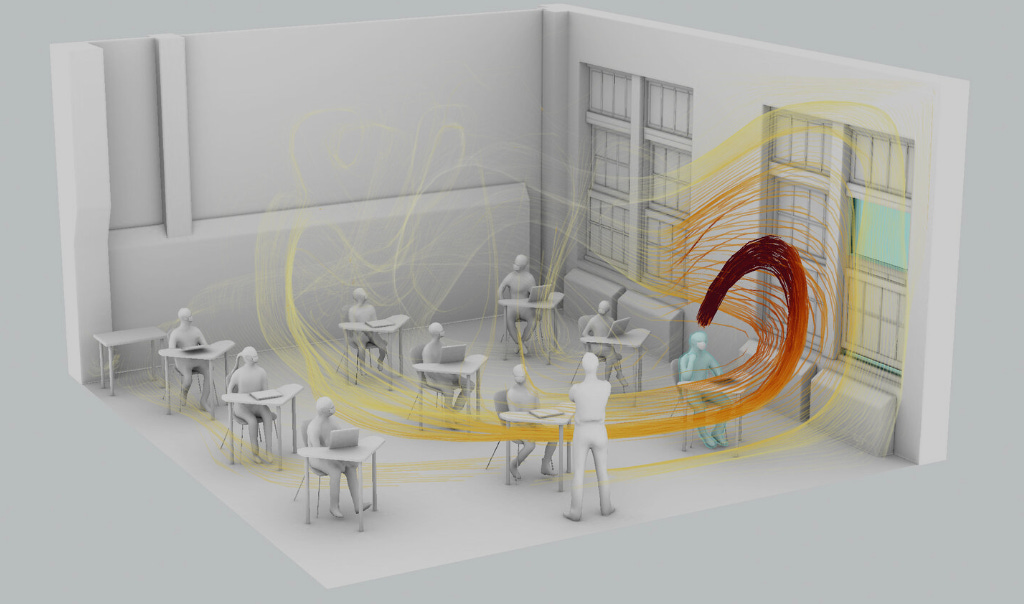

An example of this, which was a Peabody finalist last year was “Reopening Classrooms” which exists both as an online ‘scrolly tell’ experience and an AR Instagram filter.

This immersive AR explainer places the user inside an airflow simulation data visualisation, giving a unique first person perspective into how contaminants spread. It was a story that was placed across print, digital and then into mobile phones via the NYTimes Instagram channel.

It was part of a collaboration with Meta, which owns Instagram. In doing so, The Times started an Instagram-driven augmented reality initiative meant to create more personal and interactive experiences for users.

Through the use of AR, which lays a computer-generated image or animation over a user’s view of the real world, the Times was able to create an immersive experience intended to produce a deeper level of understanding.

The project uses Spark AR, a soon to be discontinued developer platform owned by Facebook, which gives creators access to a suite of tools and software needed to create augmented reality filters and camera effects and then distribute them on Instagram and Facebook. The social media conglomerate is not involved in any storytelling or editorial decisions.

“We’re reaching a newer audience who is more familiar with this storytelling medium,” said Karthik Patanjali, graphics editor for special projects. Patanjali began experimenting with AR and Times journalism about five years ago. “We knew this medium had a lot of potential, but nobody had used it for journalistic storytelling,” he said. “It was all dancing hot dogs,” referring to Snapchat’s efforts to create engaging content for its users.

According to Dan Sanchez, an editor for emerging platforms at The Times, the team hopes to use AR to create an immersive hook into the journalism The Times already produces online. The idea is to make use of Instagram’s “swipe up” feature, linking long-form pieces, to reach people who might not already have a direct connection to the newspaper.

“The whole point of this project is to really dig into how we can connect the physical world to layers of visual information,” Sanchez said. “If you’re an Instagram user, you can actually see those layers of information over top of the physical world, and you can actually manipulate them and remix them, and experience them on your own.”

“If we can take a piece of evidence and put it right in front of you so that you can see it, sense it and know its scale, I think that’s pretty huge,” said Noah Pisner, a 3D immersive editor. “There’s a lot of ways we can use it to just improve the work that journalists are already doing. We want it to be something that’s additive.”

According to those on the team, augmented reality’s current role in journalism is meant to be supplemental the same way a video, a photo or a graphic might be. While it’s meant to enhance the narrative experience at the moment, some editors believe this shift toward AR indicates not only a shift in journalism, but a shift in how we obtain and view information as a whole, Patanjali said.

“You won’t be consuming information like this forever,” he said. “It’s not going to be on a sliver of glass forever. It’s going to be around you. These are all steps toward that future we’re preparing ourselves for. The world is 3-D. Why shouldn’t the information we present also be?”

However, as with the movement of trends with technology, the AR Instagram efforts of the Times have now shifted again into other areas of immersive tech. Spatial audio, AI models for journalistic reporting are taking the forefront of the R and D department.

The Uncensored Library

A different sort of immersive journalism project leverages off an existing platform to tell a story about censorship.

Non-profit organisation Reporters Without Borders built a virtual library in the video game Minecraft to give gamers access to censored books and articles.

Named The Uncensored Library, the virtual library houses articles banned in countries including Egypt, Mexico and Russia.

“The target was to reach gamers aged between 15 and 30 years old, especially in countries with online censorship, to get them engaged with independent journalism,” senior art director at DDB Germany Sandro Heierli says.

The team chose to locate the virtual library inside Minecraft, using blockchain cloud storage to prevent governments from surveilling its contents.

“The library can be downloaded as an offline map,” Heierli explained. “The offline map is then stored on a decentralised blockchain cloud storage – which is impossible to hack.”

“Once downloaded, each map can be uploaded again, allowing the library to multiply,” he continued. “So far there are more than 200,000 copies – this makes it impossible to take the library down even for Reporters without Borders themselves.”

Users can explore a vast catalogue of materials which is always being expanded, thus creating a living library, using immersive technology.

Next in part 2 … the problem with scaling immersive storytelling in newsrooms, the ethics of immersive viewers in journalistic stories and a stab at an immersive journalist’s workflow.

It sounds like most owners of VR headsets have them in a closet after using them briefly and then losing enthusiasm. Do you think this is because the technology isn't sufficient or the software isn't there to hook them?